For over 50 years, ecologists have studied and debated the mystery of the Namib Desert’s “fairy circles,” circular patches, mostly barren of grass, that have spread across 1,100 miles in the arid grasslands of Southern Africa.

Despite their whimsical name, akin to the term “fairy rings” for circular patterns of fungi found in forested areas, there are no fairies at play here. Many theories have been put forth, but two have held the most merit. One theory has looked to blame termites for these dry patches, while the other considers the grasses’ evolution. Scientists have gone back and forth for decades, but a new study offers what may finally be evidence for a clear explanation.

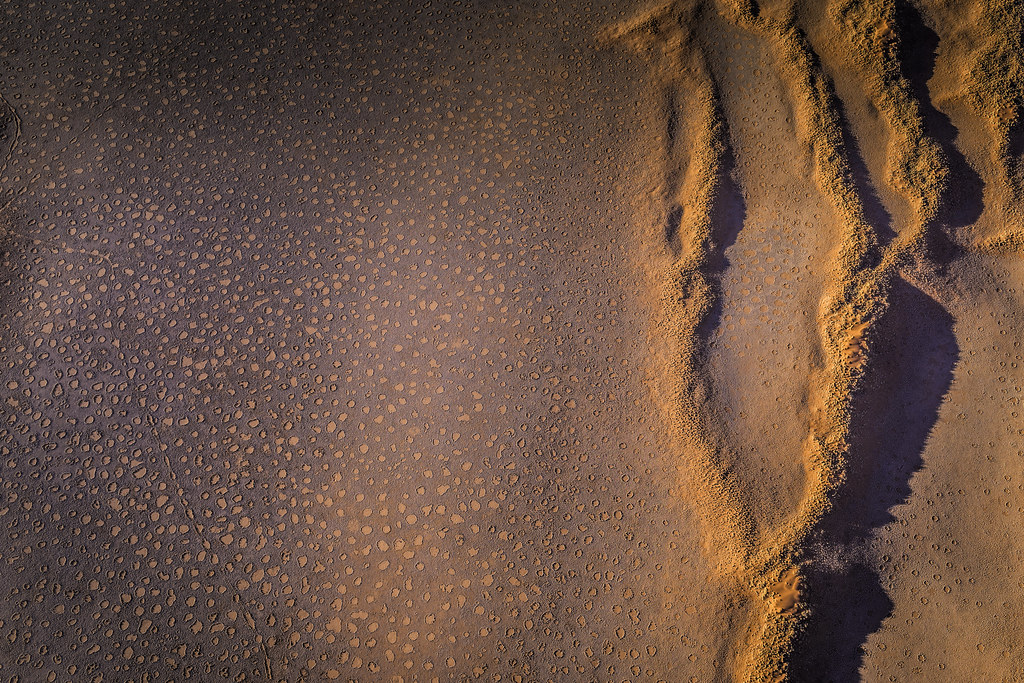

Called fairy circles, these unusual circular patches of barren land that form patterns in the Namib Desert have a whimsical name, but no mythical beings are at play here

An April 2022 drone image shows the NamibRand Nature Reserve, one of the regions in Namibia where researchers undertook grass excavations, soil-moisture and infiltration measurements.Courtesy Dr. Stephan Getzin

Stephan Getzin, an ecologist at the University of Göttingen in Germany and lead author of the study, began his research on the fairy circles in 2000. In the years since, he has published more papers on the circles, and their origins, than any other expert.

What makes the fairy circles distinctive are the barren patches within them, but the growth of grasses around them is notable as well — they have found a way to thrive in what is considered one of the driest places in the world. In previous research, Getzin and his team hypothesized that plants in the circles’ outer rings had evolved to maximize their limited water in the desert.

And for the past three years, he has spent time in Namibia tracking the growth of the grasses to find more evidence for this theory. During the drought season of 2020, Getzin and his team of researchers installed sensors that could record the moisture of the soil at around 7.9 inches (20 centimeters) deep — and monitor the grasses’ water uptake.

“We were really lucky, because in 2020 there was not much vegetation, or actually, almost any grass vegetation in the fairy circle area,” Getzin said. “But in 2021, and this year, in 2022, there was a very good rainfall season, so we could actually really follow how the growth of the new grasses was redistributing the soil water.”

Getzin’s coauthor, Sönke Holch of University of Göttingen, downloads data from a sensor in the Namib Desert in February 2021, when the grasses reached their peak biomass.

Analyzing the data from these rainfall seasons, Getzin’s team found water from within the circles was depleting fast, despite not having any grass to use it, while the grasses on the outside were as robust as ever. Under the strong heat in the desert, these well-established grasses had evolved to create a vacuum system around their roots that drew any water toward them, according to Getzin. The grasses from within the circles, which attempt to grow right after rainfall, meanwhile, were unable to receive enough water to live.

“A circle is the most logical geometric formation which you would create as a plant suffering from lack of water,” Getzin said. “If these circles were squares, or low, complex structures, then you would have a lot more individual grasses along the circumference. … The proportional area is smaller than if you grow in a circle. These grasses end up in a circle because that’s the most logical structure to maximize the water available to each individual plant.”

The study called this an example of “ecohydrological feedback,” in which the barren circles become reservoirs that help sustain grasses at the edges — though at the expense of grasses in the middle. This self-organization is used to buffer against the negative effects of increasing aridity, Getzin said, and is also seen in other harsh drylands in the world.

In response to the ‘termite theory’

The termite hypothesis, meanwhile, suggested that fairy circles are generated by sand termites that damage grass roots, and was well received among other scientists. However, a 2016 study of similar fairy circles in Australia found no clear links to the pests. Getzin’s latest research came to similar conclusions.

“We have an example where it rained only once, the grasses came up, and then after eight or nine days, the grasses only within the fairy circles had started dying,” Getzin said. “When we (excavated) these grasses carefully and looked at the roots, none of these grasses had any root damage by termites — but still, they died. Our results clearly state, no, these grasses die without termites.”

Twelve continuously recording soil-moisture sensors, installed at regular intervals at a 20-centimeter depth, track a section of the desert connecting two fairy circles.Courtesy Dr. Stephan Getzin

Getzin and his team also found the roots from young plants within the circles to be longer than those on the outside. This suggests, according to Getzin, that the grasses had created longer routes in an attempt to find water — further evidence of their competition with the outside ring’s grasses in the water-scarce desert.

While the evidence brought forth from the study is a step forward, scientists — Getzin included — believe there is still more research that could be done. That said, Getzin told CNN that it’s time for him to move on to a new challenge.

“With the fairy circles in Namibia, as well as those seen in Australia, the plants are modifying the soil moisture distribution and thereby increasing their survival chances, and we can call this sort of ‘swarm intelligence,’” Getzin said. “Plants do make intelligent patterns and geometric formations, and I will continue to work in this direction.”

Near the fairy circle area in Namibia, for example, researchers have also found a different species of grass forming in large, circular rings after rainfall. “It’s a completely different grass genus, but it forms identical circular formations,” Getzin said. He is looking to research this process during Namibia’s next rainy season of 2023.

Source: edition.cnn